Business Education at

Wake Forest University

Explore our undergraduate and graduate business programs, where students from widely diverse backgrounds and interests learn to use business to make a difference.

Undergraduate Degrees, Minors, & Programs

Nationally-ranked Bachelor of Science degree programs in Accountancy, Business and Enterprise Management, Finance and Decision Analytics. NEW FOR FALL 2026: Minor in Business, Minor in Accountancy

Master of Business Administration

Offered in Winston-Salem and Charlotte across three program formats, the #1 part-time MBA program in North Carolina is designed specifically for working professionals.

Master of Science in Accounting

Open to any major, kickstart your accounting career with world-class faculty, premier internship opportunities and unmatched CPA pass rate success.

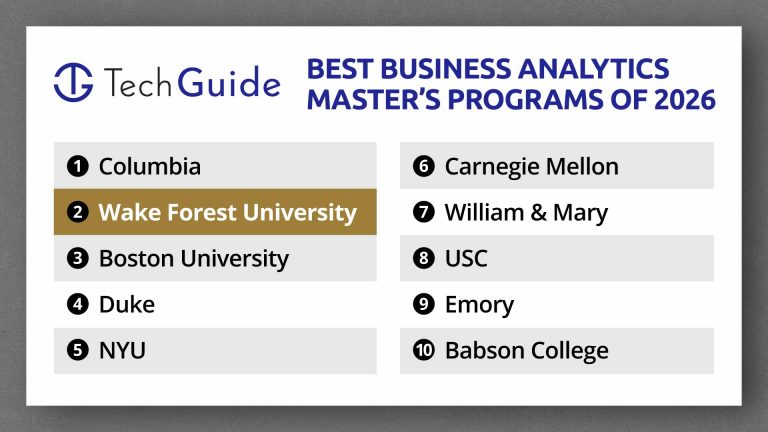

Master of Science in Business Analytics

Explore advanced methodologies for taking data from insight to impact across a range of functions, including finance, marketing, operations and human resources.

Master of Science in Management

A 10-month, STEM certified/OPT eligible program designed specifically for non-business majors and business minors who want to excel in today’s marketplace.

Pathways with Business

Explore how you can amplify any major with our diverse array of business program options.

School of Business Rankings

Our world-class programs are routinely recognized in major national and international rankings.

#1 and Top 20

Top 15

#2

#5

#2

#1 CPA Pass Rate

#1 in Big 4 Recruiting

Top 20

Top 10

Thought Leadership

We create a vibrant culture of inquiry, embracing interdisciplinary and discipline-based research and providing thought leadership to address business and organizational issues and key societal challenges.

Featured

Research

Explore a few of the groundbreaking ways our faculty uses research to address business and organizational issues and key societal challenges.

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Harvard Business Review

Harvard Business Review

Journal of Business Research

Journal of Business Research

Research Policy

Research Policy

Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting

Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting

Business & Professional Ethics Journal

Business & Professional Ethics Journal

Our academic centers drive thought leadership and create an unrivaled connection to the market

At the cutting edge of academic research & impact

Allegacy Center For Leadership And Character

We believe a strong character is as vital as strong achievement. The Allegacy Center develops future leaders who prioritize integrity, resilience, and service, preparing students to lead with purpose in any setting.

Center For Analytics Impact

Powerful data is the driver behind inspired action. The Center for Analytics Impact turns insights into ideas, providing hands-on experience solving real problems with real data, while helping businesses make smarter and more efficient decisions.

Center For Private Business

Through expert-led programming, strategic advising, and community partnerships, the Center for Private Business supports the success of businesses that span generations.

Center For The Study Of Capitalism

How can capitalism evolve for the good of all? This center explores that question head-on, uniting scholars and thought leaders who examine how markets, policy, and purpose can coexist in a rapidly changing world.

School of Business News

Ask an Expert: ‘What Is the 2026 Economic Outlook for Households?’

(WFDD)

What Causes Panic Buying? Study Says Lack of Confidence in Quick Restocking

(The Charlotte Observer)

Are Women Board Members Risk Averse or Agents of Innovation?

(Fast Company)

Upcoming Events

Join the School of Business for a broad assortment of events and happenings that advance the practice of business.

Grad Meets World: Meal Planning with Culinary U Triad

Grad Meets World is a program with synchronous and asynchronous content about preparing graduate students for life in and beyond Wake Forest School of Business. For current pre-experience graduate business students only. Unlock the power of nutritious eating and effective meal planning with Culinary U Triad!

Pavel Haas String Quartet

The Pavel Haas Quartet is revered across the globe for its richness of timbre, infectious passion and intuitive rapport. Performing at the worlds most prestigious concert halls and having won six Gramophone and numerous other awards for their recordings, the Quartet is firmly established as one of the worlds foremost chamber ensembles. Tickets: $5-$25; Free with WFU ID Wake Forest University and Medical School faculty, staff and retirees receive FREE admission for themselves and one guest to each Secrest Artists Series performance. WFU and Medical School Students receive FREE admission for themselves. We encourage those with a WFU ID to pre-register so we can keep track of available seats for the community at large. Our concerts regularly sell out. Those with a reserved ticket receive priority admission.

The Wake MBA Preview

Join us to experience our evening and hybrid MBA programs in action. You’ll connect with current students and take part in a faculty-led session with Associate Professor Kyre Lahtinen on Finance That Fuels Growth: Your Career with the MBA Finance Concentration. Experience the classroom dynamic, see how our faculty bring the curriculum to life, and take away insights you can apply to your career immediately. Hors doeuvres and drinks will be provided.

Piedmont Environmental Alliance Earth Day Fair 2026

Please visit the Special Collections & Archives booth at the Piedmont Environmental Alliance Earth Day Fair where we will have a popup exhibit along with special collections coloring cards, buttons, magnets, and stickers.

Earth Talks

Earth Talks is a series of short, student-led presentations that are focused on sustainability topics. Each talk is led by a Wake Forest student or group of students who are eager to share their knowledge, passions, or research with others in the Wake Forest community. Register for free at https://cvent.me/2myaZ0. Stay up-to date on this event on Instagram at @SustainableWFU and online at https://sustainability.wfu.edu/earth-talks/. **This event is part of Wake Forest Universitys annual Spring Celebration. Learn more about the month of festivities at https://sustainability.wfu.edu/earth-month/

Spring 2026: Commencement

Spring 2026 Academic Calendar: Important dates and deadlines for the Wake Forest College (Undergraduate College) and School of Business undergraduate programs. Please visit the Registrars Office website at registrar.wfu.edu/calendars/ for the most up-to-date academic calendar information and exam schedules.

School of Business Social Media

Follow our social media channels to stay current on everything happening at the School of Business.

Explore Further

Considering a business program to strengthen your career prospects? Interested in the world-class research being done by our faculty? Or just want to speak with someone to learn more about the School of Business? Here are a few more areas to explore.